Linux Filesystem Structure & Troubleshooting

When you rent a hosting server and pop open a shell, the first thing you face is the Linux filesystem. It’s not just a hierarchy of folders—it’s the backbone of data integrity, performance, and security. Whether you’re managing a colocation box, understanding the Linux filesystem at a syscall level helps you diagnose why a disk is full even after you deleted files, or why a web server returns 403. This guide strips away the fluff and goes straight into inodes, directory structure, and battle-tested troubleshooting for hosting environments.

1. The Root Hierarchy: Directories That Matter in Hosting

The Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS) defines where everything lives. For a hosting server, certain directories demand attention because they can fill up or become security holes.

- / – The root. If this fills up, the system becomes unstable. Always keep an eye on it.

- /home – Where user data (like websites) resides. In shared hosting, this is often the largest partition. If not separated, a single user can fill the entire disk.

- /var – Log files, mail spools, and temporary runtime data. In a busy hosting server,

/var/logcan grow by gigabytes per day. Attackers also love to write brute-force logs here. - /tmp – World-writable directory. Mount it with

noexecandnosuidto prevent malicious scripts from running. - /etc – Configuration files. Not usually a space hog, but wrong permissions here can break the entire server.

Hosting providers often use separate partitions for /home and /var to prevent a log flood from crashing the OS. Use df -h to see how they’re mounted.

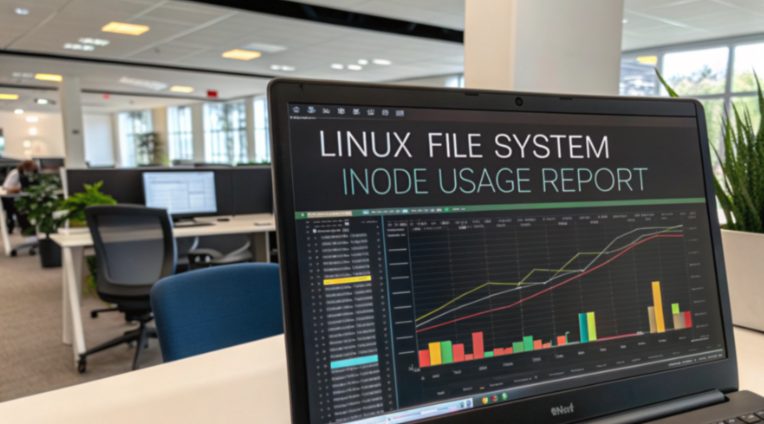

2. Inodes and Blocks: The Atomic Units

A file in Linux consists of metadata (inode) and data (blocks). The inode stores everything except the filename and the content: permissions, ownership, timestamps, and pointers to the data blocks .

Each filesystem has a fixed number of inodes created at format time. If you have millions of tiny files (think session files or email spools), you can run out of inodes even if df -h shows free space. This is a classic hosting pitfall.

# Check inode usage

df -i

Filesystem Inodes IUsed IFree IUse% Mounted on

/dev/vda1 3276800 3276800 0 100% /When IUse% hits 100%, the kernel refuses to create new files or directories—even empty ones. The fix? Find directories with massive small files and either delete them or re-format with more inodes.

Find directories with high inode count:

- Navigate to the suspected partition (e.g.,

/var). - Run

find . -xdev -type f | cut -d "/" -f 2 | uniq -c | sort -n. - Zero in on the culprit (often

/var/spoolor/var/lib/php/sessions).

3. Permissions and Ownership: The Security Layer

Linux permissions are the first line of defense in a multi-tenant hosting server. Every file is assigned an owner, a group, and three sets of rights: read (4), write (2), execute (1) . Misconfiguration leads to 403 errors or, worse, data leaks.

- Symbolic notation:

chmod u+x script.shadds execute for the user. - Octal notation:

chmod 644 filegives rw-r–r–.

Special bits are crucial in hosting:

- Setgid on directories:

chmod g+s /home/projectensures new files inherit the group, useful for team collaboration. - Sticky bit on /tmp:

chmod +t /tmpprevents users from deleting each other’s temp files.

Real-world hosting scenario: You upload a PHP script via FTP but get a 500 error. Check the file’s owner. If the web server runs as www-data but the file is owned by user:user, you need group read access. Often, setting permissions to 644 and ensuring the file is in a group that includes www-data solves it .

4. Disk Full? Here’s How to Dig

A full disk is the most common outage cause in hosting. But sometimes df shows 100% while du sums up to far less. That’s a classic “deleted file held open” scenario .

- Check disk usage:

df -hidentifies which partition is full. - Find large directories:

du -sh /* 2>/dev/null | sort -h. Drill down:du -sh /var/* | sort -h. - Locate files over 100M:

find / -type f -size +100M -exec ls -lh {} \; - If df says full but du disagrees: a process still holds a deleted file.

lsof | grep deletedshows them. Restart the associated service (e.g.,systemctl restart httpd) to release the space .

In a hosting environment, log files are the prime suspects. Use logrotate aggressively and consider remote logging to avoid filling /var.

5. Filesystem Check and Recovery

Unclean shutdowns (power outage, kernel panic) can corrupt the filesystem. The next mount may force a fsck, but sometimes you need to intervene manually. For ext4, use fsck only on unmounted filesystems .

Procedure for a root filesystem:

- Boot into rescue mode (most hosting providers offer a recovery shell).

- Run

fsck -fy /dev/sda1(replace with your partition). The-fforces check even if clean,-yanswers “yes” to all repairs .

For LVM volumes, you can create a snapshot and check the snapshot while the original is mounted . This is advanced but keeps your services online during a check.

# Example LVM snapshot + fsck

lvcreate -s -n root_snap -L 1G /dev/vg/root

fsck -fy /dev/vg/root_snap

lvremove -f /dev/vg/root_snap6. Performance Tuning for Hosting Workloads

Hosting servers often deal with mixed loads: many small files (HTML, PHP) and a few large ones (logs, backups). Filesystem choice and mount options matter .

- File system type: ext4 is the safe, general‑purpose choice. XFS shines with large files and high concurrency (good for a mail server or big database) .

- Mount options: Adding

noatimein/etc/fstabeliminates write operations on every read, boosting performance on both HDD and SSD . - I/O scheduler: For SSDs, use

none(ornoop). For spinning disks,deadlineusually gives better latency under load . Change it withecho deadline > /sys/block/sda/queue/scheduler. - Swapiness:

sysctl vm.swappiness=10tells the kernel to swap only when memory is really tight, reducing disk I/O .

Don’t blindly tune; monitor with iostat -x 1 to see await and util%. If await spikes over 20ms on an SSD, you may have a controller issue or need to tune the queue depth.

7. Special Scenario: Read-Only Filesystem

Sometimes a filesystem remounts itself as read-only during an I/O error. This is a safety mechanism to prevent corruption. If you see “Read-only file system” errors, check dmesg for disk failures. Often, it’s a precursor to hardware failure.

Immediate action: remount as read-write to try to get data out: mount -o remount,rw /mountpoint. But if the underlying device has errors, this may fail. At that point, replace the disk and restore from backup.

8. Automation and Monitoring

Proactive monitoring beats reactive firefighting. Set up cron jobs to check disk and inode usage daily:

#!/bin/bash

# Save as /etc/cron.daily/diskcheck

df -h | awk 'int($5) > 90 {print "Disk nearly full: " $0}' | mail -s "Disk alert" admin@example.com

df -i | awk 'int($5) > 90 {print "Inode nearly full: " $0}' | mail -s "Inode alert" admin@example.comAlso monitor the number of deleted files held open. A sudden spike might indicate a buggy process leaking file descriptors.

Conclusion

The Linux filesystem is a well‑crafted piece of engineering, but it demands respect. From inode tables to permission bits, every detail can become a bottleneck or a security hole in a hosting environment. By mastering the commands and concepts outlined above, you turn filesystem troubleshooting from a black art into a systematic process. Keep an eye on Linux filesystem health, and your server management will be far less reactive.